Hello! From here on it’s not as neat.

THE BEGINNING

I stood in front of the mirror for a long time before heading out, wearing the bright red wetsuit. For some reason I had expected someone to wait for me outside. A collegue, a manager, or just a curious soul. I was alone.

I spotted the mail bag from my porch, neatly washed up by the flag, laying in the sand according to plan, dragged with the sea current from there to here.

I picked it up and went back inside. I made coffee, put on a warm sweater, and stationed myself outside. All the letters came out of the bag without water damage.

The sun heated my face, the seagulls were screeching above my head and I smiled. This was the perfect, easy job. I stacked the letters -26- and folded open some maps that I had bind together in a book.

Nearly everybody came out to greet me that day. They were eager to get to know me. We complained about the big city, the digital economy and smartphones in general. I explained this was my dream job because I love swimming, hiking, and the beach.

I ended my route at the supermarket where I bought as many groceries as I could carry. I ate a baguette while walking home, not feeling bothered to cook dinner.

At ten in the evening I was a bit drunk and I stood in line for the phone booth. One of the authors was reading a new scene to her editor. It was so moving I started to cry. She perked up a bit when she noticed, but we politely ignored each other. When it was finally my turn I called my parents to tell them I was incredibly happy, and asked them if they could read out the subtitles of the movie they were watching until I ran out of coins.

DRAWINGS OF THE SCENES AND WORDS

The second day I overslept, somewhat according to plan. Yesterday’s shift had lasted ten hours. It must have been because I had gotten lost a few times, and had spent so many hours introducing myself. This morning I walked to the flag in my pyjamas. No mail bag. I felt dumb for expecting to be lucky twice in a row, and returned home to put on my wetsuit. I swam around until I noticed something bright red. The bag was stuck in a vortex. I dove down and pulled it to me. I had been informed the last bit of the post current was a loop that often caught the mail, letting it spin around in a blockage.

Out of curiousity I considered diving in the vortex. I felt it pull me if I got very close. I decided to wait a few weeks, until I had become a stronger swimmer, and maybe ask someone on the beach to keep an eye out for me.

The plan was to do this shift in under five hours. Unfortunately I got held up quite a bit. I was asked to deliver some news from person to person. Joyce told me a story one time, let me repeat it, corrected my intonations, let me tell it again, before approving and sending me over to Agnes, who lived only two houses away.

The next day I was forced to describe Agnes’ response to the story in details. How was her body language? Did she laugh? Can you imitate her facial expression when you described the loaf of bread? Why didn’t you pay better attention? It would be useful if you became better at telling stories.

And so I practiced everybody’s mimicry, voice, hand gestures, body language, way of walking. I moved slower when I imitated Ann, learned to tumble over my own words when doing George. After two years I mastered Dennis’ nervous tremble which always worsened as the sand sculpture tournament got closer -he was part of the planning committee. I carried props: sunglasses, normal glasses, two different kinds of hats, a woolen sweater and a flanel shirt.

AS THE DAYS BECAME SHORTER THE LETTERS GREW LONGER

The darkness of winter makes everybody feel lonely, even the islanders. They started gossip just for the sake of generating more messages, and my shifts could last up to thirteen hours.

I had been told that several of the islanders have a genetic mutation that results in an exceptionally bad sense of direction. There are many dog owners depending on their pets to guide them back when they left the house. Another general characteristic of the islanders is that they are moody. After years of intense conflicts it was decided to make a communal effort to decrease the amount of encounters between people.

It had become almost a taboo to visit each other. They became avid letter writers instead. If one was feeling argumentative there were always the tourists coming and going. Or the post courier.

Agnes lost her reading glasses my first winter and she had become my favorite address to visit. We broke the unofficial rules against social gatherings and ate lunch together. I read her the letters she received from her people on the mainland. Full of memories, news from her family and friends. I wrote replies with a golden fountain pen with her name on it.

After Agnes recovered her reading glasses Max lost his. It became a long letter exchange between the two of them before Max finally believed Agnes had not robbed him. Agnes sent him a long list of suggestions and one of them led to finding them. Max was so ashamed of his misplaced anger he didn’t open the door for five days when I was sent to deliver him stories. I wrote them in the sand in front of his house. DRAWINGS The sixth day he came outside to meet me and complained about his violated privacy. I apologized without meaning it.

Everybody was always home at the hour I usually came to them.

After a few months I had a hang of everybodies accents and communication styles. The islanders seemed to consider my verbal messages as neutral. Though even the order of the words influenced how something was perceived. Sometimes I felt too powerful: if I exaggerated someone’s expression the recipient of the message responded differently. When I was tired I could not convey the right energy, which tainted the original message.

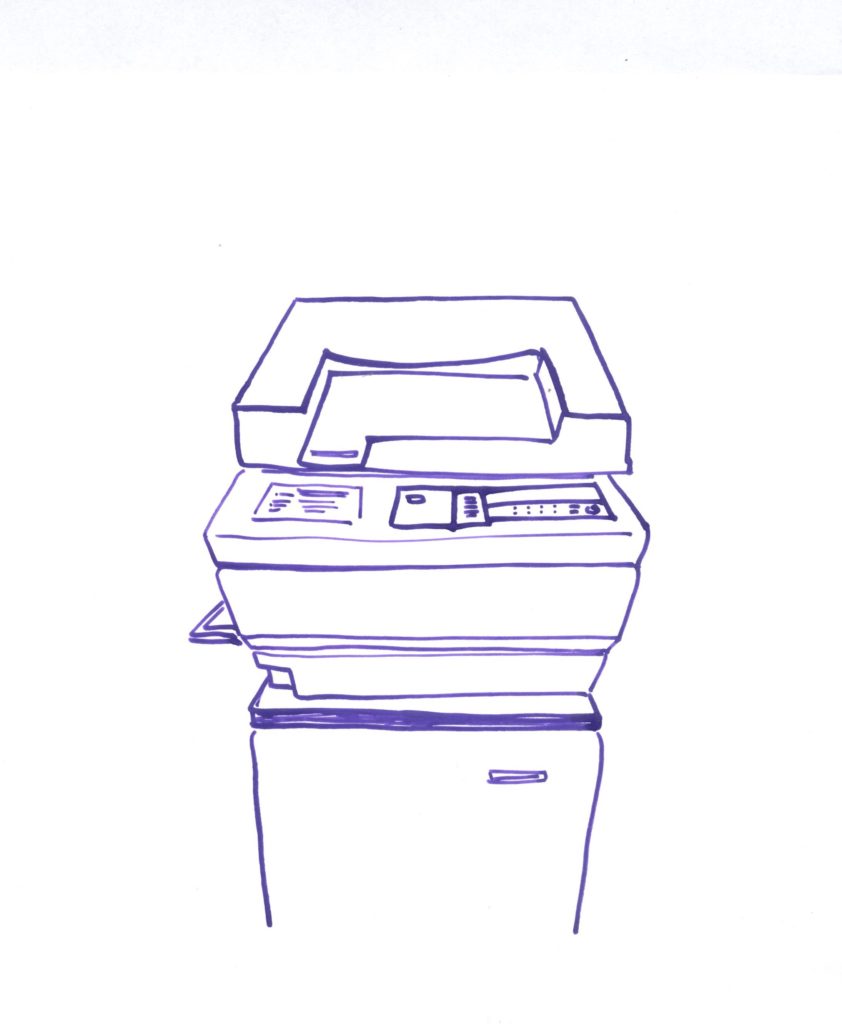

All residents were on the board of the island. The meetings were scaled down to just two a year. Most other verbal communication went through me. After some gruelling long shifts that would not have been as long if I only delivered the actual post in my bag, I spotted a copy machine in the supermarket.